Metro in the Windows 8 Developer Preview

So, on the one hand, this is a great time for Microsoft and Design. We finally have an overarching design language we can be proud of, and the company has made impressive strides in getting many of its notoriously independent product groups to embrace it. So Windows, Office, Xbox, WinPhone, and dozens of others will all be getting the new look shortly. And there have never been more senior, principal, and even partner level UX people in the company.

So why am I worried?

I’m worried because Microsoft has always been about the ecosystem play – the big tent – and not about the boutique. And I don’t think the ecosystem – both inside and outside of Microsoft – is ready for Metro.

To understand the concern, let me take you on a little walk down memory lane. Our journey starts a little over a decade ago, back in 2001, when Microsoft released XP. At that time Microsoft create a new design language called Luna. Remember Luna?

|

| Luna theme in XP |

And here lies the seed of our problem. Luna was easy to implement, and hard to screw up. As a design, it was very forgiving. You could have controls that were not quite aligned, screens that were too dense, icons where you didn’t need them, and so on, and your stuff would still pretty much fit in. It was a low bar, and thus was easy to hit.

Later, when we did what became Vista, we had a new design language called Aero. This was a little more ambitious. For Aero, we were not going after new computer users. People already knew how to use a computer. We wanted to make the computer experience more comfortable and stylish. Aero added more emphasis on layout and white space. We added more subtle visual cues. Overall, we turned down the volume (visually) on the UI to make the workspace more calm. We added transparency and a little animation. It looked great.

|

| Aero in Windows Vista |

At that time, I had a discussion with Don Lindsay, who was one of the primary architects of Aero, about the cost of the design. Don was of the opinion that software was different from most manufacturing. You could increase the quality of the design without increasing any other production costs. I disagreed.

Aero was harder for teams to get right. You had to understand about effective use of white space, which was hard for teams without a graphic designer. You had to understand what to make subtle and what to make obvious. You needed to understand motion. But that was just the up-front cost. These designs were also harder for developers to implement. Animation is harder to code than static screens. Old techniques like automated dialog layout that looked acceptable in Luna looked like crap in Aero. And then there was the testing cost. In Luna, small errors didn’t really jump out. If a few things were out of alignment, it wasn’t so glaring. But in Aero, even small mistakes were very noticeable.

So truly embracing a new design language really requires a serious commitment of time and expense to get that language right. This was not budgeted in the Vista planning process, and as a result most teams came up short. It was even worse outside Microsoft. Many third party developers simply did not have the time and money to properly make their products conform to the Aero design language.

And now we get to Metro.

Metro (for those who don’t know) was originally designed for the Zune. It is kind of an evolution of the design thinking in Media Center, Microsoft’s television UI.

|

| Media Center UI |

http://www.flickr.com/photos/everydaylifemodern/page8/

The first thing to point out is that doing this sort of design is hard. It difficult from a visual perspective. You have to understand a lot about typography. Things like the weight, leading, and kerning start to matter. Empty space, negative space, balance, hinting, flow, and so on all become crucial in that the lack of them will immediately jump out. Most people who didn’t graduate from design school don’t even know these things exist. Many people who did graduate don’t use them very well. And in the starkness of Metro, there is no place for mediocre visual design to hide.

But the visual part is just the tip of the iceberg. The real challenge is that Metro requires a deep rethinking of the information architecture itself. You can’t just take the same information you have today and let a graphic artist “make it Metro”. It doesn’t work that way.

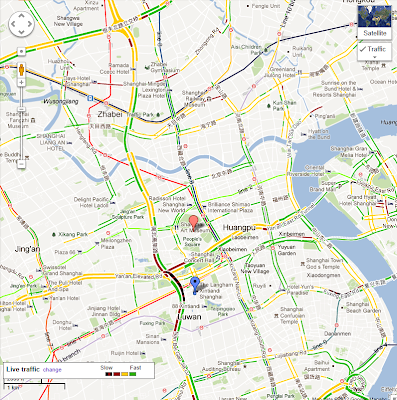

For example – here is a map of Shanghai that is showing the subway maps and stops.

|

| Map of Shanghai |

|

| Map of Shanghai - Metro-style |

Doing this requires someone who is not only an expert in design, but also an expert in the domain of maps and even in the city itself. It also requires a certain boldness and confidence – confidence to go into a meeting and convince a bunch of non-designers that all of those things really don’t matter.

So now look back at that street map. THAT is your product now. Who on your team is going to make it into the subway map for Metro? Is there any individual or even set of individuals who know enough about design, and enough about your product, to make that kind of radical redesign? And if they do exist, are they empowered in your organization to actually make that change happen? Do you have the development team that can pull it off? And does your test/QA team have the skills and tools to check for errors with highly polished design? For about 98% of current internal Microsoft teams, Fortune 500 IT groups, and even ISVs, the answer is NO.

Most teams are simply not prepared in any way - staffing, budget, etc. - to pull off great Metro redesigns. And wose - Microsoft is not communicating to them that this is even necessary. We just need to take a peek at the windows phone marketplace to see the future. For every app that does Metro nicely, there are about 1000 more that really screw it up and turn it into an ugly abomination. And those are just phone apps, which tend to be a) small and b) created just for the phone.

For desktop apps, most of the apps are going to be large existing apps. The developer is going to look for easy solutions. They are going to want something as easy as moving from WIn95 was to Luna. And god help us, Microsoft is delivering it to them. I have already been exposed to PowerPoint templates that turn your current presentation into Metro. How? By making all of the Headings into Monocolor boxes with white text in them. If that all people think of Metro, we are all in trouble.

No comments:

Post a Comment